Anatomy of Narcissism v1.0 (i) – What and How

by Philip Jonkers

Motivation

This is a report of my present understanding of the psychopathology known as narcissism. It’s an ongoing investigation as to what makes the narcissist tick. Feel free to share your insights with me, either as comments or by private communication. I might just absorb them into a new version.

What is Narcissism?

Although there are many different definitions of pathological narcissism or Narcissistic Personality Disorder floating around on the web, since it is a standard work of reference in the field of psychiatry and in spite my reservations to accepting it as the only and ultimate authority (read: “bible”) on psychiatric illnesses and disorders, I will nonetheless opt for the definition as stated in the DSM-IV:

Definition of Narcissistic Personality Disorder

DSM-IV-TR 301.81

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth edition, DSM IV-TR, a widely used manual for diagnosing mental disorders, defines narcissistic personality disorder (in Axis II Cluster B) as:[1]

- A pervasive pattern of grandiosity(in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements)

- Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love

- Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions)

- Requires excessive admiration

- Has a sense of entitlement, i.e., unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations

- Is interpersonally exploitative, i.e., takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own ends

- Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others

- Is often envious of others or believes others are envious of him or her

- Shows arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes

- Often mild to moderate paranoia, that others are out to do him in.

- Predominant “name dropper” boasting or suggestion association with people or affiliations of importance.

It is also a requirement of DSM-IV that a diagnosis of any specific personality disorder also satisfies a set of general personality disorder criteria.Wikipedia

John William Waterhouse – Echo and Narcissus

Deriving Characteristics from the Tale

The origin of narcissism traces back to Freud, who derived inspiration from the Greek Myth surrounding Narcissus, a pathologically self-absorbed young man. Since Narcissus proved to be unwilling to return the love other people had for him, “the gods” punished him by making him fall in love with his own reflection in a pool; thus he could learn to feel what it was like to love without being returned affection. Tragically, Narcissus became so much in sway of his mesmerizing self-image that he died of self-neglect.

Here is a rendition of a key excerpt of the tale:

One day whilst out enjoying the sunshine Narcissus came upon a pool of water. As he gazed into it he caught a glimpse of what he thought was a beautiful water spirit. He did not recognise his own reflection and was immediately enamoured. Narcissus bent down his head to kiss the vision. As he did so the reflection mimicked his actions. Taking this as a sign of reciprocation Narcissus reached into the pool to draw the water spirit to him. The water displaced and the vision was gone. He panicked, where had his love gone? When the water became calm the water spirit returned. “Why, beautiful being, do you shun me? Surely my face is not one to repel you. The nymphs love me, and you yourself look not indifferent upon me. When I stretch forth my arms you do the same; and you smile upon me and answer my beckonings with the like.” Again he reached out and again his love disappeared. Frightened to touch the water Narcissus lay still by the pool gazing in to the eyes of his vision.

He cried in frustration. As he did so Echo also cried. He did not move, he did not eat or drink, he only suffered. As he pined he became gaunt loosing his beauty. The nymphs that loved him pleaded with him to come away from the pool. As they did so Echo also pleaded with him. He was transfixed; he wanted to stay there forever. Narcissus like Echo died with grief. His body disappeared and where his body once lay a flower grew in it’s place. The nymphs mourned his death and as they mourned Echo also mourned. Source

Salvador Dalí – Metamorphosis of Narcissus

The prime characteristics of narcissism that we may derive from the meaning of the tale are:

Fatal and delusional self-absorption:

The narcissist is hopelessly infatuated with a perception of himself (footnote 1) that is not grounded in actuality. Narcissus falls in love with a shallow representation that exhaustively resembles a shallow and flattering representation of himself (his own mirror image), an image of himself that conveniently ignores the gloomy truth that the inner being of narcissus is nowhere near as praiseworthy as his appealing exterior. Indeed, since he is incapable of loving any other being his character must be like that of constantly disapproving kind, critical of everything and everyone. Thus it can safely be assumed that his unseen interior, his character, is rooted in fear rather than love. By being susceptible to be mesmerized by the mere exterior of a being that perfectly mirrors himself, Narcissus proves to favor an effectively inflated and idealized representation of himself as the darkness of his ugly interior is conveniently ignored against the brightness of his beautiful exterior. In addition, he demonstrates the shallow nature of his interests, including those of the romantic kind, in other beings.

The tragedy of the narcissist is that reverence to what is nothing more than an illusion ultimately leads to his own demise. Or, as self-confessed self-aware narcissist Sam Vaknin puts it, he commits “the ultimate narcissistic act: self-destruction in the service of self-aggrandizement.”

Unresponsive to love:

The narcissist is handicapped at being at want to return the love people show to have for him; his self-absorbed and disapproving nature makes him blind to the affection from other people and make him incapable of reciprocating. He suffers from what Erich Fromm calls “impotence of the heart,” i.e. he is incapable of making people love him and instead seeks to control and manipulate them.

Sees people as objects:

The narcissist is only satisfied when things go according to plan, his plan of course. If not, he is displeased. As such, his relentless insistence on perfection, makes him too anxious to leave room for loving people. Consequently, he lacks empathy and has no genuine respect for people, as empathy and respect both have to have a basis of love for one’s fellow human being. And therefore he is unable to appreciate the personhood of people. He rather views them as objects, preferably extensions of his own will.

Only accepts actions that mirror his will:

Yet another main defining characteristic of the narcissist, a deeper meaning that can be deduced from this tale is that he only loves that which perfectly mimics his own ideal course of action. In the context of the tale, Narcissus only loves that which perfectly mirrors his own preferences. In other words, he is extremely picky and accepts and approves (“loves”) something on the condition that it is perfectly conformal to his own will.

But this, by definition, is conditional love that we’re talking about then. One may rightfully wonder: can this kind of love that the narcissist professes also be regarded as genuine love?

Suppose your boss is an N and you do your utmost best to gain his approval. But, due to his obsession with insistence on perfection, the narcissist does not nod in approval that quickly. So here you are, working your butt off trying to please someone who’s extremely critical and demanding and thus exceedingly hard to please. Most of the time, the narcissist will cause you to feel miserable for delivering, what he considers, below standard work. Perhaps every so often, when you somehow miraculously manage to meet all the stringent conditions imposed by the narcissist, you may earn his gratitude. And so by being extremely demanding, he sets the tone of an anxious and tense working atmosphere. The narcissist, figuratively speaking, radiates anxiety and tension to his employees and the rare event of you succeeding to do gain the favor of the boss is likely to flood your brain with feelings of relief and pleasure. It is thus very much like a drug addict finally getting his fix after a long period of forced abstinence. The druggie also experiences relief washing over him as the withdrawal symptoms are yet again dismissed to the background. The appropriateness of the analogy with the drug addict serves as a confirmation that the kind of love the narcissist dispenses, conditional love, in a practical sense equals addiction.

In general, this is a recurring theme for any kind of relationship with a narcissist. By his very demanding nature and his stinginess to show “love” — the narcissist, wittingly or unwittingly, works to make addicts of the people who end up in a relationship with him.

But the narcissist not only makes addicts, he is one himself too. I will expand on the link between narcissism and addiction, in section Narcissism versus Addiction.

Frans D.J. Francken – The Idolatry of Solomon

Narcissism and Idolatry

The word idolatry comes (by haplology) from the Greek word εἰδωλολατρία eidololatria parasynthetically from εἰδωλολάτρης from εἴδωλον eidolon, “image” or “figure”, and λάτρις latris, “worshipper”[4] or λατρεύειν latreuein, “to worship” from λάτρον latron “payment”. Wikipedia

Hence, idolatry simply means image-worship.

wor·ship

1. reverent honor and homage paid to god or a sacred personage, or to any object regarded as sacred.

2. n.a.

3. n.a.

4. the object of adoring reverence or regard. freedictionary

I further suggest that the practice of worship presupposes a state of submissiveness to the entity of worship.

Hence idolatry is the practice of submissively paying homage to- or revering the image; regarded as sacred and hence perfect, incontestable and beyond criticism.

Narcissism is about submitting to- and revering a presumed sacred image of the self; it is worship of an (inflated, distorted, idealized, etc.) image of the self, or worship of a self-image, or self-image worship, which is: self-idolatry.

The following metaphor captures the essence of the narcissist.

Shrine of St Valentine

Shrine-Metaphor

The narcissist may be imagined as the host to his own proverbial mobile shrine. Picture in the center of the shrine a huge portrait of the narcissist in which his most flattering features are embellished and distorted in a grandiose manner so as to inspire both awe and envy.

People in the his social environment (his audience) are invited to enter the shrine and instead of paying a regular cash entrance fee, they pay by worshiping the portrait. As such, the portrait is maintained in proper condition as it would otherwise quickly wither away and fall apart together with its host whose very reason for existence hinges on its welfare.

“Narcissism appears realistically to represent the best way of coping with the tensions and anxieties of modern life, and the prevailing social conditions therefore tend to bring out narcissistic traits that are present, in varying degrees, in everyone. These conditions have also transformed the family, which in turn shapes the underlying structure of personality. A society that fears it has no future is not likely to give much attention to the needs of the next generation, and the ever-present sense of historical discontinuity — the blight of our society — falls with particularly devastating effect on the family. The modern parent’s attempt to make children feel loved and wanted does not conceal an underlying coolness — the remoteness of those who have little to pass on to the next generation and who in any case give priority to their own right to self-fulfillment. The combination of emotional detachment with attempts to convince a child of his favored position in the family is a good prescription for a narcissistic personality structure.” (Lasch; p.50)

How is Narcissism Brought Into Existence?

What motivates the narcissist to devote one’s life to the construction and maintenance of a fantastic and lofty self-image? To answer this question we need to examine the human childhood. This section is largely inspired by Sandy Hotchkiss’ book on narcissism called Why is it Always About You? The Seven Deadly Sins of Narcissism. Especially chapter 8, Childhood Narcissism and the Birth of Me served as a source of information.

When we are toddlers we enter into a developmental stage what Freud called Primary Narcissism. This is a normal form of infantile narcissism in which we unwittingly view our caregivers as inseparable extensions to our own being. At our beck and call, our primary caregiver (usually the mother) fulfills our needs much like servants tending to the call of their master. In a narcissistic sense they more-or-less loyally mirror our needs and so there’s no incentive yet for us to perceive them as being separate and distinct from ourselves.

We need their symbiotic attachment in order to derive a necessary level of confidence to go and set out on our wobbly legs to explore the environment. Call it the mommy-takes-us-by-the-hand stage of development, if you will. This protective narcissistic proverbial bubble gives us a certain sense of invincibility, a much needed attitude in order to confront an environment that is filled with potential danger and as such is quite threatening to, what is in actual fact, a very vulnerable toddler.

The child derives comfort and support from a securely attached mother, who assists him in coping with the intense joy and excitement as well as the frustration of being small and vulnerable in an expanding toddler world. The attachment of the child to the mother equips him to be able to cope with the stress-burden belonging to the exploratory behavior committed with a disproportional zest that is characteristic of infantile narcissism.

The function of the attached mother therefore is to help regulate her child’s moods and emotions to, on the one hand, dampen over-excitement as well as distress, and, on the other hand, not pamper the child too much so that it also learns to cope with a bit of tension and agitation. This two-staged practicing period (happening around 10-12 and 16-18 months of age) is essential for the development of a separate sense of Self, and is the time during which the part of the brain that regulates emotion, is hardwired for life.

In the course of the practicing period, the role of the mother will shift from being a playmate/nursemaid to a more prohibitive “no-no” role. When mother gives the toddler a “cold shower” act of socialization for doing something “bad”, an initial mood of elation is likely to give way to what are called “low arousal states”, resembling a toddler version of somberness or even mild depression. But this is a normal development nonetheless, and this training-phase helps the mind of the toddler to learn to conserve energy and to inhibit excessive emotion. By moving in and out of these low arousal states, the child learns to depress intense or unpleasant feelings with ever less assistance from Mommy Dearest. This helps him to develop psychological autonomy.

The Soothing- versus the Shaming Inner Parent

The goal of socialization is to stimulate the child to try and live in harmony with the rest of the world. In order to do this, undesirable behavior needs to be restrained and discouraged as much as possible. The designated tool of persuasion for giving up pleasure for an undesirable act, is the powerful emotion of shame.

Hotchkiss writes:

“For the child, the first experience of shame is a betrayal of the illusion of perfect union with Mother that has persisted up to this point. Her beloved face now may radiate shame, extinguishing joy and exuberance in an instant. Instead of being pumped up by Mother, the child now feels deflated, even injured. This is an essential and instructive wound, however, which teaches the child that Mother is not only separate but different, and that his place in the world will not always be on top of the mountain.” (Hotchkiss; p.41)

Fig 1. The toddler (“Me”) is being shamed for doing something bad. Right before being shamed he “imagined” himself to be omnipotent, in a infantile kind of way of course. This is because his infantile mind is unable to see the separateness between himself (the valiant “Knight”) and his powerful primary caregiver (“Mom”, the “Queen”). The act of shaming serves to burst that bubble of normal infantile narcissism and promotes the development of the more realistically grounded individual. This is called the separation-individuation process.

The shaming experience helps to pop the bubble of the toddler’s infantile form of narcissism: the “omnipotent” toddler-version of a self-indulgent and relatively recklessly exploratory bravado-attitude (see Fig.1) that seems to correspond most closely with Freud’s idea of the ID. Since unmitigated shame may result in lasting psychological damage however, it is of the utmost importance that the wound be inflicted gently.

After the mother has shamed the child, a soothing follow-up response (“soft-looks, warm touches and kind words”) is necessary in order to help the toddler deal with his shaming experience in a healthy manner. The cycle: initial elation for doing something that is considered bad, followed by the mother socializing the child through shaming and the ensuing recovery — constitutes a positive learning experience which fosters the development of a healthy Self.

This recovery part is crucial for the toddler to learn that hurt feelings can be mended again and that the caregiver can be trusted. Emotionally, the young child needs compassionate help in managing emotions and protection from overwhelming feelings until his brain matures sufficiently for him to be able to do this on his own. Small doses of shame followed by soothing, help the child gently and responsibly deflate his infantile narcissism towards the development of a more realistic sense of Self. As he progresses through the practicing period, the toddler becomes more and more independent from the caregiving mother. This is called the separation-individuation process.

In the words of Hotchkiss:

“The first two or three years of life are the age of narcissism when the child’s underdeveloped Self and lack of awareness of the otherness of others are normal. Grandiosity, omnipotence, magical thinking, shame-sensitivity, and a lack of interpersonal boundaries come with the package. We are meant to outgrow this stage, but we need the help of parents who can tolerate and love us while we get through to the other side. We need them to hold the boundaries that we don’t yet see, to recognize who we really are and can be, to help us manage shame and contain rage, and to teach us to live in a world of others. When that doesn’t happen, we can become stuck in childhood narcissism. Failure to complete the separation-individuation process is what leads to a narcissistic personality.” [emphasis mine] (Hotchkiss; p. 45)

When a child has been shamed but lacks a loving and forgiving follow-up, it is left with a festering psychological wound. The failure to mitigate shame leaves the toddler inclined to interpret the behavior as being unforgivably shameful. This may be traumatic for the child–the first narcissistic injury if you will, and lack of mitigation reinforces the immoral severity of the shameful act. Although it should be understood that the experienced degree of the trauma also depends on the capacity of the child to sustain disciplinary action. If the child has a rather fragile and vulnerable psyche then it is only reasonable to expect that the impact of the trauma is more severe than a child who possesses a more robust psychological constitution. In the former case the soothing part is more important than with the latter.

The toddler registers the emotionality of the shaming mother — shaming facial expression, agitated voice and embarrassed mannerisms — deep into his memory through his senses. I suspect that this perception of a shaming caregiver (or caregivers) gives rise to the formation of a sort of internally projected mental presence of the shaming parent; one that is reinforced with every recurrence of an unsoothed shaming experience. Call it the emergence of the shaming inner parent if you will.

Hotchkiss also suggests the coming into existence of such an inner authoritarian presence:

“The child’s normal narcissistic rages, which intensify during the power struggles of age eighteen to thirty months — those ‘terrible twos’– require ‘optimal frustration’ that is neither overly humiliating nor threatening to the child’s emerging sense of Self. When children encounter instead a rageful, contemptuous, or teasing parent during these moments of intense arousal, the image of the parent’s face is stored in the developing brain and called up at times of future stress to whip them into an aggressive frenzy. Furthermore, the failure of parental attunement during this crucial phase can interfere with the development of brain functions that inhibit aggressive behavior, leaving children with lifelong difficulties controlling aggressive impulses.” [emphasis mine] (Hotchkiss; p.21)

Without our faculty of mimicry it would be impossible to assimilate cultural elements, e.g. karate techniques, and propagate them from person to person. Pictured is a karate class in Okinawa with the Shuri Castle at the background.

Indeed, one should not forget that our learning potential crucially relies on our ability to mimic. By virtue of imitating our parents, and later our peers, we absorb the cultural environment around us like a proverbial sponge. One might call this process, that never needn’t be complete, adaptation to the local cultural climate. More than our self-reliance craving egos perhaps like to admit, our lives — especially our childhoods, when the need and potential for learning is the greatest — revolve around the activity of copying each-other activities, behavior and later opinions. In general, the propagation of culture would be impossible if it weren’t for the existence of our faculty of mimicry, which in turn relies on a strong innate capacity to, in great detail, register and assimilate sensory expressions of other people; facial expressions of our parents at first, and vocal chord sounds later on when our minds have developed sufficiently to enable us to learn our native tongue. Indeed, it would be impossible to learn something as profoundly elementary as language without our faculty of mimicry, which vitally relies on a capacity to accurately duplicate the speech sounds made by the people in our environment in general and our parents in particular. To put it succinctly and generally, we are beings of imitation.

Therefore it is plausible to assert that, even more so given its developmental significance, we do strongly register the emotionality of the shaming parent. Later in life, any experience that may be considered shaming is likely to be met with the wrath of this shaming inner parent, which is just a form of internally generated- and directed form of punishment. The child thus has been saddled with the mental burden of an inherently condemnatory and disapproving inner mental judge, a punisher. In terms of Freud’s ID, ego and Superego Structural Model, it seems justified to suggest that this prohibitively natured inner parent most closely corresponds with the Superego.

Fig 2. The nature of soothing is constructive and restorative whereas that of shaming is destructive; its precise function is to destroy the motivation for the activity or behavior which the caregiver deems to be not allowable. When soothing is applied after an act of shaming, its role is to help the child recover from the negative impact of shaming. Soothing is an act of love, shaming without soothing is an act of selfishness and fear. Soothing works to liberate, shaming without soothing works to control and suppress. Soothed shame does not obstruct the development of genuine self-love whereas unsoothed shame does; it fosters self-resentment, self-hatred, malignant self-love and self-sadism/masochism (self-shaming) or plain sadism when shaming is directed outwardly unto others through (retributive) displacement.

Therefore when the toddler has never enjoyed shame-mitigating follow-ups, a soothing inner parent has never been given chance to develop in tandem with the shaming inner parent. The subjection to shame is therefore an extra painful experience. Whereas the character of the shaming inner parent is punitive and destructive, that of the soothing inner parent is constructive and restorative. In addition, the shaming inner parent functions to control behavior, whereas the soothing inner parent works to unburden or mentally liberate the child after it has been disciplined. It is presumed to be self-evident that in order to warrant the mental health of the child, the presence of a soothing inner parent is indispensable (see Fig.2).

Fig. 3. Upper part: If shaming is applied without soothing, the unmitigated destructive effect of shaming may encourage the toddler to learn to start viewing other people as liabilities, as if they are out to punish him. Bottom part: If shaming is applied with soothing, the corrosive effect of shaming is contained and there is no cause for the toddler to learn to grow wary of other people.

If the toddler is shamed without soothing, the seeds are planted in his mind for viewing other people as being out to hurt him (see Fig. 3). By its destructive character, shaming is an act of hostility and if the subsequent soothing part remains lacking and the more he is exposed to shaming the more likely the toddler will come to harbor negative perceptions of other people, potential punishers if you will. He therefore is more or less forced to view other people with caution and even as liabilities. The seeds of mistrust have been planted, and prepare him to receive people defensively (, aggressively). Even those who show genuine affection toward him are reinterpreted as ones who still may have nefarious ulterior motives of secretly wanting “to do him in,” and so never really can be trusted. The narcissist-in-the-making thus is severely handicapped at being able to imagine that other people view him in a loving and amiable way. I will address this issue again in section The Love-Hate Relationship with his Audience.

As a way to prevent future recurrence of having to feel raw unmitigated shame, the mind of the toddler is urged to develop his own means to compensate and dampen the reception of the mentally corrosive shame. Another way of putting it, is that he is forced to learn how to deal with his rudely deflated narcissistic bubble. You could say that the child is plunged into a psychological crisis marked by a need for improvisation and a sense of selfish emergency.

The child’s strategy of choice consists of walling off these intolerable, raw and unadulterated feelings using several crude ego-defensive mechanisms. Whenever shame threatens to seep into his life again, he learns to seek refuge behind a protective barrier of denial, coldness and rage. Alternatively, the shame may be outwardly projected, away from the vulnerable Self. Someone else is blamed instead, so that the child does not have to deal with it himself. It is an attempt to redirect persecuting eyes away from oneself onto others, thus bypassing the painful need to admit one’s error and to adjust oneself. If and when it has become impossible to deny that the cause for blame is not to be found in other people as much as it is in oneself, the blame-game called projection may however foster the development of self-hatred if the capacity to forgive oneself is absent.

In other words, to deal with shame without parental soothing, the child retracts into a (self-)deceptive world of make-belief, acting (histrionics/theatrics) and insincerity (lying).

Referring to the apparent shamelessness of the narcissist, Hotchkiss comments:

“More typically, the shamelessness of the Narcissist comes across as cool indifference or even amorality. We sense that these people are emotionally shallow, and we may think of them as thick-skinned, sure of themselves, and aloof. Then, all of a sudden, they may surprise us by reacting to some minor incident or social slight. When shaming sneaks past the barriers, these ‘shameless’ ones are unmasked for what they really are – supremely shame-sensitive. That is when we see a flash of hurt, usually followed by rage and blame. When the stink of shame has penetrated their walls, they fumigate with a vengeance.” (Hotchkiss; p. 6)

I suggest that this unhealthy and improvised reaction to shame, rooted in a lack of parental loving concern for the growing child, is to be regarded as the psychological basis for the coming into being of the grandiose and fictional self-image.

“The N I write about probably never did a thing, unless there was something in it for him. He simply did not bother. He started from a position of weakness, in that he had a huge inferiority complex, but the pretentiousness of his facade gave the impression of enormous self-confidence.” NPDQuotes

Construction of the Self-image

Unsoothed ossified shame, the first narcissistic wound(s) rudely deflating the child’s narcissism, is likely to arouse sentiments of inferiority with respect to people who do not seem to burdened by the same fate as he is. Consequently, the child may start to become envious of supposedly normal people. The very presence of these “normal” people, whose proverbial grass always seems to be greener than his own, then turn out to be painful reminders of how he could have ended up himself. He could have been one of them, hadn’t he suffered a damaging blow to his vulnerable psyche. And by becoming distraught he may start to resent their very existence. And so starts to view them as a liability, a menace, undesirable. Depending on the strength and resilience of his mental health, or better: lack thereof, he may even go so far as to blame them for causing him to feel envious, and making him feel miserable. (footnote 2)

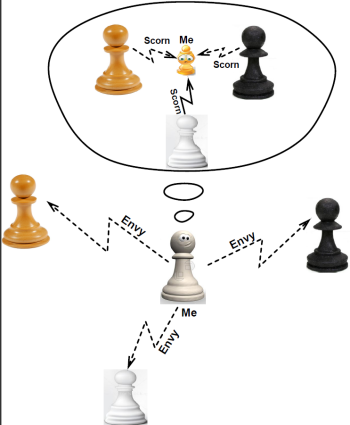

Fig. 4. After having sustained sudden deflation of his narcissism, the toddler is left psychologically wounded. He feels inferior as compared to his peers and may be, or may fear to become, the target of shaming (scorn, ridicule and condemnation). This leaves him feeling miserable and so feelings of envy towards his peers, whom he holds in relatively high esteem, kick in.

As a way of dealing with the burdensome feelings of envy (see Fig.4), his mind comes up with a resolution. He starts looking for reasons to justify disqualification of the people he envies. The apparent underlying motive being that people who are not worthy are automatically not worthy to be envied. And so he may go ahead and condemn the perceived mediocrity of their lives, or at least certain visible aspects of it. However, tragically, the act of condemning their lives, forces him into a position at which he no longer can afford to try and become one of them himself. He cannot become that which he already has chewed up and spat out. It would make him not just a hypocrite, he would now have to stoop low in order to become one of them.

Note that this condemnatory attitude falls right in line with the mind of the narcissist in spe burdened with the condemnatory natured shaming inner parent. Just as he has been persecuted, he may derive some sense of gratification though engaging in persecution himself. Also note the inherent destructive nature of this type of broadly retributive behavior is. The act of shaming is a destructive act. It serves to destroy the specific motivation for doing that which has been flagged by the parent as being prohibited. And so when shaming is not compensated through soothing, parents may inadvertently encourage the character of their child to be formed with an appetite for destruction. Especially when the child is the subject of scorn coming from peers, for personality traits that he beliefs are caused by that of which he is ashamed, he may likewise develop an appreciation for scorn when he can find personality weak spots in other people. The matter then becomes a sort of retribution and, I believe, lies at the basis for sadism.

Returning to our narcissist-in-the-making, by condemning mediocrity, normalcy, he must strive for something superior; something bigger, bolder and better. And so his mind starts to seek out the justifying conditions for embracing a perception of the self which, in a grandiose manner, trumps those of the “normal” people. See it as a pathological way of wanting to get even, a kind of revenge. And as he works to see to the construction of his superior self-image, ideally, the necessity for envy is numbed.

Indeed, by being driven by a desire for vengeance, he is likely to be motivated to set out and reverse the subject- and object roles of envy. Rather than the subject, he now will strive to see himself becoming the object (target) of envy (see Fig. 5). In the narcissist’s mind, the time has now come for the normal people to become envious of him; or more accurately, to become envious of his intimidating and super-sized self-image.

In addition, the grounds for his burdensome sense of shame can be avoided as they belong to a part of him that has been tucked away and blotted out by a lofty and irreproachable new version of himself, embodied by his self-image. The act of identification with his fantastical self-image can be understood to be an attempt at psychological dissociation from his real but tainted self.

Supporting this generative route through envy, I suspect that the shaming inner parent may also be instrumental in bringing about his superior self-image. The character of this inner shaming parent — fortified perhaps by later mental impressions of shaming inner peers working in tandem with the already resident shaming inner parent, forming a shaming inner presence — is decidedly negative and prohibitive and may be an incentive for the ego to revolt through generating a challenging and self-indulging representation of himself. The inflationary defiance of the emerging self-image thus may be understood as a coping strategy of the ego intending to offset the deflationary damage done by the shaming inner presence.

Fig.5. The purpose of the grandiose self-image is to inverse the envy/scorn roles. If he can manage to persuade his peers (and himself) that he really is the very antithesis of the worm he feels himself to be, he may now become the subject of envy. If and when that happens he has a reason to put other people down and gain some sense of vindication.

Footnote 1 I refer to the narcissist as being masculine but this does not mean that I therefore believe that no feminine narcissists exist. I just prefer to keep notation simple and brief and so I choose to use “him” instead of the more proper but lengthier “him or her” or the confusing but likewise proper “them”. As it turns out, most narcissists are males anyway.

Footnote 2 Let me be clear though that I am not at all suggesting that anyone person who has experienced some sort of trauma earlier in life, by necessity, ends up becoming a narcissist. I suspect that many or even most people are quite capable of handling trauma, provided they have a resilient enough mental health, trauma coping power if you will, and are supported by loving and caring family members and/or close friends. The more defective the underlying mental constitution is and the more the support of family and/or friends is lacking, then the greater I’d regard the likelihood for traumas left unresolved, which may then promote the formation of narcissistic tendencies.

| Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 |

[…] […]

Phil this is hbnwok, good to see you are still active, I saw your hotmail got hacked, I been running around the world and stuff! Keep up the great work!

Yo wassup hardboiled 🙂 I’m still doin it you know. I’m working on a very big project right now and have been for the last 4 months straight. I hope it will be finished in 2 months.

Are you still on MSN or Pidgin? I tried to add you but some reason it failed.

Dont be a stranger and good to hear from you and whatever you do, dont get your ass all tied up in bullshit wars ok?

Take good care amigo 🙂

[…] https://philsphil.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/anatomy-of-narcissism-v1-0-i-what-and-how/ This is the post Phil posted. […]

I linked this blog post to my blog, i hope you get some views from it, I dont have that many but this is a great layout here…

i have never enjoyed reading a blog entry so much. i thoroughly appreciate this- i even joined wordpress because i found your great blog here

Thank you!

Reblogged this on egomountainbliss.

Thanks for a great informative article. my doctors think my ex boyfriend is narcissitic and the more I read, the more i think so too. it’s not an easy thing to accept or understand, its not like everyone can relate to it. Thanks for making something so confusing that little bit simplier

You’re welcome Colee 🙂

[…] https://philsphil.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/anatomy-of-narcissism-v1-0-i-what-and-how/ Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

[…] https://philsphil.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/anatomy-of-narcissism-v1-0-i-what-and-how/ […]

[…] I’ve been thinking a lot recently ‘why blog?’ What started this train of thought was a comment on one site (Can’t find the reference, sorry) where a troll said something like: “Noone cares what a narcissist like you thinks”. It got me thinking about the point of blogs. Are they just online diaries written by narcissists? […]

[…] Image credit: Phil’s Philosophy […]

[…] Image credit: Phil’s Philosophy […]

[…] Source: https://philsphil.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/anatomy-of-narcissism-v1-0-i-what-and-how/#Prime […]

[…] Phil’s Philosophy […]

[…] Image credit: Phil’s Philosophy […]