Dream-idolatry and Tally of Immoral Actions (3/4) The Great Gatsby

by Philip Jonkers

Finally learning Gatsby’s past shrouded in mystery

After he came back home, Nick found himself unable to sleep and was still awake when he heard Gatsby also being brought back home by taxi. He decided to visit his neighbor and hear the latest.

Nick: “Jay? Everything alright. . .?“

Exhausted, Gatsby turns. . .

Gatsby: “Oh, hello, old sport. Yes, yes, everything’s just fine. . . About four o’clock she came to the window; she stood there. . . Then, well, she turned out the light.“

Nick: (narrating) “I should have told him what I had just seen. But all I could manage was. . .“

Nick: “Jay. . . You oughtta go away.” (pp.119)

The person who at the beginning of the story took pride in being honest, turns out to increasingly become dishonest. By refusing to tell Gatsby the truth as to what he saw happening between Daisy and Tom, Nick lies by omission. He could have helped Gatsby to pull his lofty self a little bit away from the dreamy outlandish illusion in which he chose to float. Nick, as such, could have helped a friend-in-distress become a bit more firmly grounded in truth. And yet he chose not to do so — why not? Why did Nick choose to facilitate the continuity of Gatsby living in a fantastic kind of mental wonderland? Was it sheer selfish cowardice that prevented Nick from doing so? — or did he sense that it would be futile to tell the truth to a friend who were to have been so hopelessly trapped and thoroughly wrapped up in his own mesmerizing dream?

He helps Gatsby cover the car.

Nick: “Tonight. They’ll trace your car.“

Gatsby: (as if Nick is crazy) “Go away? I can’t leave now. Not tonight.“

Nick: “Do you understand that a woman has been killed–?“

Nick follows him from the garage toward the house.

Gatsby: “Daisy’s going to call in the morning. Then we’ll make plans, to go away together.“

Nick: “But Jay she–“

Sensing Nick’s tone, Gatsby cuts him off and banishes all doubt with intense certainty.

Gatsby: “She just needs time to think. . .“ (he continues, calm) “She’ll call. In the morning. She just needs time to think.“

Nick: “Jay–“

Gatsby: “She just needs to think. She’s going to call in the morning.” (pp.119,20)

Gatsby courageously flashes that “smile of endless possibility. . . He turns to go in but stops.“

Gatsby: “Wait up with me? The sun’s almost up. . .“

Nick: (narrating) “That was the night he finally told me the truth. All of it.“

Gatsby: “You know, I thought for awhile I had a lot of things. . . But the truth is. . . I’m empty. I suppose that’s why I make things up about myself. . . But I’ve wanted to tell you the whole story for a long time. . . You see. I grew up, terribly, terribly poor, old sport.” (pp.120,1)

He told Nick that Jay Gatsby was not even his real name, but rather a more common-sounding James Gatz — a kind of name which, to Gatsby, evidently just didn’t sound exclusive, glamorous and charming enough for the glorious and exalted sort of future he had in mind for himself. “He had changed it at the age of seventeen and at the specific moment that witnessed the beginning of his career — when he saw Dan Cody’s yacht drop anchor over the most insidious flat on Lake Superior. It was James Gatz who had been loafing along the beach that afternoon in a torn green jersey and a pair of canvas pants, but it was already Jay Gatsby who borrowed a row-boat, pulled out to the Tuolomee and informed Cody that a wind might catch him and break him up in half an hour.“ (pp.101,2)

And so, by pretending to have a fancier name than he really had, already we can see Gatsby’s willingness to pretend to be someone who was more important and more esteemed than he really was in order to help him achieve a more prosperous station of life.

Nick recalled that his wealthy neighbor had told him that, “His parents were shiftless and unsuccessful farm people — his imagination had never really accepted them as his parents at all. The truth was that Jay Gatsby of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God — a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that — and he must be about His Father’s business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.“ (p.102) (i)

{When Nick said that Gatsby “sprang from his Platonic conception of himself”, he meant that Gatsby sought to emulate what he considered was his ideal (Platonic) form. From gradesaver.com: “That is, the Platonic form of an object is the perfect form of that object. Therefore, Nick is suggesting that Gatsby has modeled himself on an idealized version of “Jay Gatsby”: he is striving to be the man he envisions in his fondest dreams of himself. Gatsby is thus the novel’s representative of the American Dream, and the story of his youth borrows on one of that dream’s oldest myths: that of the self-made man. In changing his name from James Gatz to Jay Gatsby, he attempts to remake himself on his own terms; Gatsby wishes to be reborn as the aristocrat he feels himself to be.“} (back2text)

Before he met Cody on Lake Superior, young Gatsby had been trying to earn a living “along the south shore of Lake Superior as a clam digger and a salmon fisher or in any other capacity that brought him food and bed. His brown, hardening body lived naturally through the half fierce, half lazy work of the bracing days. He knew women early, and since they spoiled him he became contemptuous of them, of young virgins because they were ignorant, of the others because they were hysterical about things which in his overwhelming self–absorption he took for granted.“ (p.102)

Finding no satisfaction in what he did and finding no solace with his present dirt-poor station of life, “his heart was in a constant, turbulent riot. The most grotesque and fantastic conceits haunted him in his bed at night. A universe of ineffable gaudiness spun itself out in his brain while the clock ticked on the wash-stand and the moon soaked with wet light his tangled clothes upon the floor. Each night he added to the pattern of his fancies until drowsiness closed down upon some vivid scene with an oblivious embrace. For a while these reveries provided an outlet for his imagination; they were a satisfactory hint of the unreality of reality, a promise that the rock of the world was founded securely on a fairy’s wing.“ (pp.102,3)

In other words, Gatsby came to convince himself that the world around him was less real than the would-be world defined by the self-hypnotizing dreams spun by his feverishly imaginative mind, an imaginary version of a world that–entirely unknown to him–was nonetheless the product of a mind quite stricken with simmering megalomania. And by working to fulfill his dreams, he would only be working toward reducing the ostensible unreality of reality. And by supposedly working to make reality less unreal, Gatsby would always be able to convince himself that what he was doing was the right thing to do, that there would be an inherent justice in his labors to make his dreams come true.

Fortune finds its way into young Gatsby’s life in the form of a friendship with millionaire Dan Cody

To the impoverished young Gatz it must have been a magical moment of revolutionary proportions when he, after having experienced only hardship and dissatisfaction with life, was able to indulge in the salvaging sight of something as unrealistically-exotic and outrageously-opportune as the anchoring of a luxurious yacht right in front of his unclean unkempt very nose! To the materialistically-deprived rag-wearing lad it must have felt as if the Tuolomee, sailed by a rich aging fellow named Dan Cody, had been sent down straight from the exquisite well-stocked chambers of heaven and had landed–with a crash and splash–squarely in front of his struggling dirty hands. James could hardly have helped interpreting what he came to have the pleasure of seeing as a sure gift from God, a divine omen which were to have let him know then-and-there that beyond a shadow of doubt splendid fortune had finally succeeded to push all the filthy clutter and stinking refuse aside and–in an almost heroic rescuing feat–had found its way into his heretofore bereft miserable life. “To the young Gatz, resting on his oars and looking up at the railed deck, the yacht represented all the beauty and glamor in the world. I suppose he smiled at Cody—he had probably discovered that people liked him when he smiled. At any rate Cody asked him a few questions (one of them elicited the brand new name) and found that he was quick, and extravagantly ambitious. A few days later he took him to Duluth and bought him a blue coat, six pair of white duck trousers and a yachting cap. And when the Tuolomee left for the West Indies and the Barbary Coast Gatsby left too.“ (pp.103,4)

Let’s suppose that Gatsby indeed did take to mean his fateful encounter with Dan Cody as a gift of God. Could he then perhaps also come to see this special event and his subsequent friendship with the millionaire as justifying evidence for the grandiose prejudice which he cherished regarding his own person: that indeed he was a true son of God? — that, after all, only true sons of God would qualify to receive heavenly gifts? By having what he thought was the kind of exceptional exotic experience which served to justify his sentiments of grandiosity, if it wasn’t so already, could his sense of entitlement–as a result–have ballooned to celestial proportions?

The dreamy somnambulist that he was, Gatsby moved through life as if he was forever drawn forward–as it were–by his eternally-enticing grandiose visions of himself hoovering in the imaginary space that could be thought to exist a few steps above and in front of him. And if something highly beneficial yet unforeseen would happen in his life, could Gatsby not just have been tempted, but have been extremely prejudiced to interpret the occasion to mean that the road of life which he–because of the event–had chosen to go down into (while in dreamy sleepwalking-mode), would also be the kind of road that had already been sanctioned in advance by God? — and, what’s more, that he had been given green light by God himself to not just go ahead and tread down that road slowly and cautiously but that he would be perfectly free to even to do so in enthusiastic cavalier fashion? — that he would be perfectly free to let it all hang out and gallop down that road with perfectly reckless abandon?

In other words, while being fully-equipped with the kind of self-confidence which he had gained by brute-force artificial self-elevation (courtesy of his megalomaniacal Narcissism), could it be that Gatsby came to believe as being the ultimate truth–what nevertheless was a delusion–that he was perfectly-entitled to heedlessly ditch the exercise of caution and prudence as to what might possibly be waiting ahead on that road he chose to dash headlong down to, the one that laid out his personal future? And so when suddenly he succeeded in having Daisy back in his life, could his sense of celestial entitlement have deluded him into prematurely believing that his future marital union with Daisy was already a sure thing, a done deal, and that the task of telling Daisy’s husband that she never were to have loved the poor guy was also but a small and insignificant task? — because, after all, all she ever were to have done was love Gatsby, only Gatsby, and nobody else but Gatsby.

Cheated out of Cody’s inheritance, could sustaining Narcissistic injury have been the reason for launch into a life of vindictive and compensatory crime?

After having served the “alcoholic millionaire Dan Cody“ for “five years“ as his loyal companion (pp.74,5), Gatsby hoped to inherit a good sum of money when the wealthy owner of the Tuolomee–his “best friend“ (p.70), at the time–passed away. However, unfortunately for him, he never received a penny. Having no knowledge of the law, he “never understood the legal device that was used against him“ and Cody’s wealthy inheritance ended up in the pockets of an another intimate of Cody (one of his gold-digging mistresses). “He was left with his singularly appropriate education; the vague contour of Jay Gatsby had filled out to the substantiality of a man.“ (p.104)

Fitzgerald made no mention at all in his book as to what happened to Gatsby as a result of what must have been a hugely-disappointing development in his life — Gatsby were to never actually have told Nick about this, no doubt, dark episode of his life. And so we are left with guesswork. If we make the highly-plausible assumption that Gatsby was factually engaged in the practice of some kind of Self-idolatry–one which in all likelihood had a rather strong Narcissistic component having a rather pronounced sense of entitlement (perhaps even of celestial proportions)–then would it not seem perfectly justified to suspect that Gatsby must have sustained quite the Narcissistic wound, as the “victim” of so complete a bypassing as to Cody’s attractive wealthy inheritance, to end up completely empty-handed?

After all, here was Gatsby having all these bedazzling dreams of “ineffable gaudiness“ (p.102) and then–as if by divine intervention–he had had the fortune of finding Cody, had consequently become used to and smitten with opulence and abundant materialism . . . and yet had suffered the abhorrent fate of being “cheated out“ (p.76) of the inheritance coming from the millionaire whom he had served–and faithfully so–for no less than five long years. His fantastical dreams were still there, as was his colossal sense of entitlement, but no matching fortune was at his disposal. While deluding himself into believing (as being the solemn truth) that he–as a “son of God“—one way or another was entitled to possess wealth (and lots of it too), could it then be plausible for him to have reasoned that if he was cheated out of the kind of wealth which he felt (strongly) should be his to keep, then he would be strongly inclined to feel justified to have his revenge in the form of doing a little bit of cheating on his own in order to actualize the prophecy that was virtually written in the stars: that he was destined to acquire the kind of wealth which he–until that point in his life–so painfully and so humiliatingly had been deprived of?

What Gatsby seems to have failed to see, however, was that he–in a state of grandiose self-delusion–came to utterly blind himself from realizing that the practice of rapid capital acquisition through illegal and morally-dubious means stands to conflict with the qualification criteria of being–what civil people would naturally consider–a gentle man? — a man who is respectable because he acts in ways which are generally considered respectful, . . . the kind of man that the likes of Daisy would find an eligible man.

Alternatively, could Gatsby have convinced himself that if he would have to stoop to a career in crime and as such forfeit his claim to genuine gentlemanship, that if he would have to kiss goodbye to the possibility of deserving to be found truly respectful, then that to him would still be a reasonable price to pay for being able to fulfill his all-important dreams? Owing to his past as a poor young man, having a kind of past which left him with (what he considered) no real personal respectability, could Gatsby have been content with having a pretentious respectability that only appeared genuine? — meretricious instead of meritorious a kind of respectability?

Gatsby meets Daisy, “the first ‘nice’ girl he had ever known”

“In the silvery pre-dawn, Nick and Gatsby trail slowly toward the end of the dock.“

Nick: (narrating) “It was also that night that I became aware of Gatsby’s. . . extraordinary gift for hope.“

Gatsby: “. . . I can’t describe to you how surprised I was to find out that I loved her, old sport. And that she loved me too.“

Nick: (narrating) “A gift that I have never found in any other person. . .“

Gatsby: “I never realized just how extraordinary a nice girl could be.“

Nick: (narrating) “And which it is not likely I shall ever find again.” (p.121)

He told Nick the following about Daisy:

She was the first ‘nice’ girl he had ever known. In various unrevealed capacities he had come in contact with such people but always with indiscernible barbed wire between. He found her excitingly desirable. He went to her house, at first with other officers from Camp Taylor, then alone. It amazed him—he had never been in such a beautiful house before. But what gave it an air of breathless intensity was that Daisy lived there—it was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him. There was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year’s shining motor cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered. It excited him too that many men had already loved Daisy—it increased her value in his eyes. He felt their presence all about the house, pervading the air with the shades and echoes of still vibrant emotions. (p.150)

What kind of attitude could underlie a statement like this: “it excited him“ that “many men had already loved Daisy—it increased her value in his eyes“? Why did Daisy’s popularity with boys, his peers in the military in particular, increase her value in his eyes? I can never be sure as to what went on in his heart and mind of course, but one thing that could have fueled his enthusiasm for her is that–if she were to end up by his side–Daisy would make a fine woman to show off, ideally suited to proudly go flaunt around town with and impress other men. The more men there were who already would have loved her, the greater the odds were that if he–with Daisy at his arm–were to come across one of her former lovers then the sight of once a loved girl being intimate with another guy– a little bit of a snob even, from the looks of it–might just trigger a strong emotional reaction in the former lover at hand.

The guy could, for example, react with an exaggerated sudden respect for Gatsby — for having managed to win over the heart of the girl once dear to him (but had lost since). Alternatively, the guy could react with jealousy and give the discernible impression to now have a ruined day for seeing the girl he once loved getting all lovey-dovey with another guy — the kind of guy who–from the looks of it–even thinks he owns the freaking place.

Either way, courtesy of the beautiful little beaming doll at his arm, the competitive side to Gatsby might just be able to have an enjoyable experience in exercising such subtle kind of power over other men (power to impress). Whereas he used to be painfully-invisible to other people when he was miserably scurrying around as a poor rag-clad lad, especially invisible to people of note, he now has the solace of having a head-turning romantic partner by his side who almost literally forces the people they encounter to recognize his existence, if they hadn’t done so already, by his mere intimate association with her. As I said, I do not know if–or, to what extent–Gatsby saw Daisy in such a light, ultimately in the light of her ending up as his Trophy–wife, but his admission is consistent with this possibility.

What is also interesting is that Daisy would be the “first ‘nice’ girl“ in his life. As to why that was, I find it entirely possible that his Narcissism caused him to express himself in the form of an overblown self–importance which happened to have had a kind of turn-off-effect on some girls (perhaps many) and so they would naturally resent having to interact with him, his perceived-to-be imperious self. Hence, whenever he would encounter them, he would be strongly-inclined to interpret such type of girls as not being “nice girls” at all. Instead, such girls would much sooner strike him as being rather standoffish and, ironically-enough, maybe even “arrogant“.

Alternatively, in sharp contrast, his overbearing Narcissism might also have managed to attract the easily-humbled kind of girl, the pleasing submissive kind which naturally would tend to gravitate to the comfort and protection offered by domineering type of males like himself, the type of girl which would have a serious knack to want to spoil him (too much). In his own words, according to Nick, Gatsby “knew women early” — meaning that he was sexually intimate with women from an early age. He must have managed to get laid quite a few times because, due to his ease at getting sexual pleasure, “since they spoiled him he became contemptuous of them, of young virgins because they were ignorant, of the others because they were hysterical about things which in his overwhelming self–absorption he took for granted.“ (p.102)

Somehow Daisy must have been the first accessible girl he had come across, who did not strike him as “ignorant“, nor “hysterical“, nor “arrogant” — i.e., someone with an easy–going nature, who knew her ass from her elbow, and yet was not too cocky about it; someone who was compatible with his “overwhelming self–absorption“.

But he knew that he was in Daisy’s house by a colossal accident. However glorious might be his future as Jay Gatsby, he was at present a penniless young man without a past, and at any moment the invisible cloak of his uniform might slip from his shoulders. So he made the most of his time. He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously—eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand.

He might have despised himself, for he had certainly taken her under false pretenses. I don’t mean that he had traded on his phantom millions, but he had deliberately given Daisy a sense of security; he let her believe that he was a person from much the same stratum as herself—that he was fully able to take care of her. As a matter of fact he had no such facilities—he had no comfortable family standing behind him and he was liable at the whim of an impersonal government to be blown anywhere about the world. (pp.150,1)

Again, Gatsby gladly and eagerly–albeit also guiltily–seized the opportunity to present himself as being someone he was not, a person of elevated rank — who’d normally had no hope of reaching out to off-limits high-rank girls like Daisy, owing to his near-poverty status. He used his uniform to disguise his “despicable” status and give himself the appearance of being an interesting eligible young gentleman; a young man who was attractive at least in a military sort of way and therefore would supposedly also be attractive in a noble kind of way. After all, a consequence of the romantic times in which he still lived, he would shortly be off to fight instantly-heroic battles against the world’s assembled wicked forces of depravity and darkness, the evil geopolitical spectre that with its venomous claws was having Europe in the sort of stranglehold which left it just begging for a military-styled delivery provided by outside countries such as the very one which he had the fortune of living in right now. Gatsby could at least rely on the goodwill and moral supremacy which his uniform was beaming out into the world. In so many words, he would be one of the good guys and his uniform served as proof positive.

Again, Gatsby gladly and eagerly–albeit also guiltily–seized the opportunity to present himself as being someone he was not, a person of elevated rank — who’d normally had no hope of reaching out to off-limits high-rank girls like Daisy, owing to his near-poverty status. He used his uniform to disguise his “despicable” status and give himself the appearance of being an interesting eligible young gentleman; a young man who was attractive at least in a military sort of way and therefore would supposedly also be attractive in a noble kind of way. After all, a consequence of the romantic times in which he still lived, he would shortly be off to fight instantly-heroic battles against the world’s assembled wicked forces of depravity and darkness, the evil geopolitical spectre that with its venomous claws was having Europe in the sort of stranglehold which left it just begging for a military-styled delivery provided by outside countries such as the very one which he had the fortune of living in right now. Gatsby could at least rely on the goodwill and moral supremacy which his uniform was beaming out into the world. In so many words, he would be one of the good guys and his uniform served as proof positive.

Nick: “What was in the letter?“

Gatsby: “The truth, the reason why after the war, I hadn’t been able to return–“

In the clouds overhead, the image of Daisy, in the bathtub with the dissolving letter. . . And now, we can see what Gatsby wrote in that fateful, last letter: “Daisy, the truth is. . . I’m penniless.”

Gatsby: “I asked her to wait until I’d made something of myself. But– She was young, there was so much pressure.” “You see, I felt married to her. . . That was all.“

Nick: (narrating) “It had all been for her. The house the parties, everything.“ (pp.121,2)

This must be Gatsby’s noble streak. At first–while hiding his shamefully low social status–pretending to be Prince Charming, a male peer worthy of Daisy’s hand. And then, after all, still prove to have the courage to tell Daisy that he was but a penniless slob. He knew the ramifications of this profoundly self-humbling confession to Daisy. In all likelihood, she could not possibly bring herself to marry him if he were poor, belonging to an inferior class — a comparatively shameful socioeconomic status. And so it speaks greatly in favor of Gatsby’s character to have had the courage to reveal his honest naked self to her. To have been willing to expose himself in such vulnerable a manner must really count as proof positive of his genuine love for her; he must have loved her so much that he, rather than seeking to exploit her with his pretentious shenanigans (as he might have done with other girls), he precisely went to protect her from them.

And yet it appears that he also feared losing her, because he had been willing to go down a dubious and risky criminal route in order to get as rich as he would have to be (or, at least, think he would have to be) in order to grant himself a credible chance to court Daisy again, to win her hand along with her heart. Then again, to the extent that he wasn’t purely spurred on by raw greed, in a romantic and dramatic sort of sense, it might speak favorably of Gatsby to have been willing to take such great risks on what is, by definition, a perilous road to attain an unusually-prosperous station in life.

Nevertheless, Nick would later say that Gatsby were to also have claimed, while referring to Tom’s relationship with Daisy, “I don’t think she ever loved him“. “You must remember, old sport, she was very excited this afternoon. He told her those things in a way that frightened her — that made it look as if I was some kind of cheap sharper. And the result was she hardly knew what she was saying.” “Of course she might have loved him just for a minute, when they were first married — and loved me more even then, do you see?“ (p.154) Contrasting his noble streak, this shows how immodestly Gatsby felt himself to be; that he declared himself entitled to take up prime residence in Daisy’s heart, that–since she had loved him once–she, as a result, forever would feel wed to him in her heart the way he felt wed to her in his heart. . . and that their love would be of such special and durable quality that it would persist and dominate even if she would marry another.

What is remarkable is that Gatsby simply did not know that Daisy had once actually loved her husband. In principle, it is possible that he previously had asked her and that she had squarely lied to him at the time. However, what perhaps is more likely is that he had never actually even brought himself to ask her about her true feelings for Tom — a disinclination to give that kind of attention to other men which would be fully consistent with his Narcissism, his self-centeredness, his “overwhelming self–absorption“.

In all those times they spent together during the affair, he would then always have been only interested in her to the extent that she was capable of reflecting him back, the extent that she would mirror him in his all-consuming love for his own precious Platonic (ideal) imaginary world. His all-enveloping commitment to Narcissistic Self-idolatry would then have prevented him from even acknowledging the existence of Tom as someone equally worthy as he was. It appears that Gatsby had been utterly incapable of imagining that Daisy might have been capable of actually loving the man whose existence he actually preferred to neglect, belittlingly calling him “the polo player“ (p.109).

The agonized ashen assassin strikes and the curtain drops with a loud bang . . .

In the meanwhile, the sun was just beginning to spill over the horizon–lighting up their view of East Egg–and Nick was showing signs of wanting to leave. Without having had any sleep that night, he knew he “wasn’t worth a decent stroke of work“. Nevertheless, Nick–brave or foolish, whichever the case may have been–made up his mind to at least present himself at work. He promised Gatsby to call him from the office later that afternoon. “We shook hands and I started away. Just before I reached the hedge I remembered something and turned around.” Nick shouted across the lawn, “They’re a rotten crowd“, “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.“ (p.156)

“I’ve always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we’d been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of color against the white steps and I thought of the night when I first came to his ancestral home three months before. The lawn and drive had been crowded with the faces of those who guessed at his corruption—and he had stood on those steps, concealing his incorruptible dream, as he waved them goodbye.“ (p.156)

Daisy had yet to call when Jay decided to take a swim in his pool, which he were to have failed to use all season long. However, just in case she would call–after all–and would do so at the very same time he was in it, he had the telephone conveniently brought down to the pool. In spite of Gatsby’s evident phenomenal tenacity to cling to his optimism, Nick believed that Daisy would not call and believed also that Gatsby himself–in a most sober mood, deep down inside–didn’t believe she would call. “I have an idea that Gatsby himself didn’t believe it would come, and perhaps he no longer cared. If that was true he must have felt that he had lost the old warm world, paid a high price for living too long with a single dream. He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is and how raw the sunlight was upon the scarcely created grass. A new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about . . . like that ashen, fantastic figure gliding towards him through the amorphous trees.“ (pp.163,4)

At that precise moment wailing old Wilson, delirious by grief and demented by unconscious guilt, suddenly crept from out of the bushes and–unbeknownst to Gatsby–slowly but surely made his way to the pool. When the phone finally did start ringing and Gatsby did think that it was Daisy calling him after all, an sullen zombie-like Wilson coldly and decisively aimed his gun and pulled the trigger — shooting Gatsby in the back, thus making him fall back into a pool hereafter increasingly spoiled by human blood. After callously offing a defenseless Gatsby like a dog, Wilson turned the gun on himself and ended his miserable own life.

And so it was that Gatsby came to his violent demise, dying while being convinced that Daisy had finally come to the decision to grant him that one salvaging call, the call that were to affirm her preference of him over Tom, the one call in which he–by then–had invested his whole life, his whole future, the one call which promised to set everything right in his life again, the all-or-nothing call on which his singular reason for existence clung so desperately . . . when, tragically, in actual fact, it was just faithful old Nick calling from the office to learn the latest news.

What would have happened if–before he died–he would have known that it wasn’t Daisy who sought to speak with him? What would have happened if he were to have managed to convince himself that Daisy did not and probably would not call him? If he had accepted the outcome that Daisy were to never be at his side, as he absorbed the accompanying disappointment of likely traumatic dimensions, would he have minded getting killed? If not, if he would not have objected, then Wilson’s killing of Gatsby would have a decidedly suicidal feel to it. If this observation is correct, then Gatsby might just have gotten the feeling that he had blown his life by having made the kind of gamble which turned out to have a fatally-costly outcome for him — he had lost, and lost hard.

Serving as a complete scapegoat: life violently extinguished as well as personal image annihilated

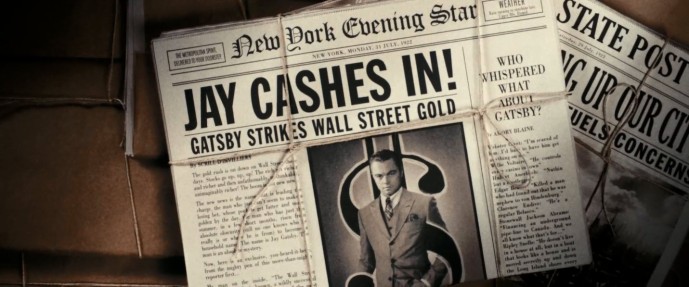

In the wake of his murder, Gatsby’s name would also be shown no mercy. His public image was unceremoniously cut to bits and pieces, shredded and all mangled up until there was nothing left but a bad memory. “The headlines were a nightmare. . . They pinned everything on Gatsby:“

- “BOOTLEGGER KILLS MISTRESS!”

- “HIT AND RUN”

- “GATSBY GUILTY OF MURDER!” (p.126)

With a heavy heart Nick looked back at the mess the press made of it. “And there was nothing I could say except the one unutterable fact that none of it was true. . .“ (p.126) Nick “rang“, “wrote“ and “implored“ (p.128) all those people who had known Gatsby, to give the man his last honor. “But not a single one of the sparkling hundreds who had enjoyed his hospitality all summer, attended the funeral . . .” (p.129)

Perhaps it may not be so hard to understand why all those “sparkling hundreds“ neglected to show their faces at the service. While Gatsby had thrown all those parties, he at the same time seemingly barely made an effort to show up on the social gatherings he saw to having organized — let alone make his presence known openly and, for example, explicitly welcome his guests by way of an advertised open and public appearance. But it was of course never Gatsby’s intention to act as a welcoming host and “lose himself”, so to speak, in his own energetic alcohol-fueled parties.

The giant alcohol-fueled human gravity device beaming out into the world wave-upon-wave of attractive human excitement

Rather, all those party people lumped together at Gatsby’s crazy place constituted what might be called a huge human beacon. From Gatsby’s point of view, they unwittingly served as nothing more than actors in a grand subtly-organized spectacle of human attraction, one big merrymaking machine made up entirely of human parts and which had the express purpose of radiating to the outside social environment attractive human excitement, wave after wave, “all weekend, every weekend.“ (p.27)

Maddened by an romantic hunger quenchable in only one single way, Gatsby threw all those parties–he deployed his, if you will, human gravity device–in order to specifically attract, with the aim of retaining, the attention of just one girl. And after having deployed his festive human beacon for a sufficient number of times, once he had managed to attract the notice of that one exquisite human specimen he was after so desperately, when he had been able to get his former lover back in his arms again, once Gatsby and Daisy started seeing each-other again, he simply ceased giving them; the string of extravagant parties he was known for hosting that summer came to an abrupt screeching halt, whadda-ya-know, just like that. He simply switched off his giant human magnet from one moment to the next. No explanations were given. The lights went out and that was that, end of story.

Not surprisingly, Gatsby had no trouble doing so. Indeed, as he told Nick: “I couldn’t care less about the parties!“ (p.85) Gatsby probably did not really care about the garden-variety in-the-main uninvited guest attending his parties either. One likely contributing factor for Gatsby to retain such a dissociated attitude towards the fun-loving party public he catered to, could very well be the fact that he was quite knowledgeable of the aggravating rumors about his person that they–on his very own parties, even–were spreading around, vicious acts of badmouthing in which he invariably was painted in rather hideous and despicable light (e.g., propagated by Catherine, p.23; and Jordan’s East Egg friends, p.30), “all those bizarre accusations“ Nick would be hearing, earlier on in the story — they were nothing but “a pack of lies“, assured Gatsby. (p.39)

If indeed it was true that he would be gossiped to death–as it were–on his own parties, then it would be rather understandable if Gatsby happened to not be too keen on mingling at his own parties very often. And from the perspective of the kind of guest who liked to have wildly-depreciatory opinions of Gatsby, especially if they would not be deterred from actively expressing them among other party guests (i.e., if they would actively spread malicious gossip about him), would therefore out of a sense of guilt–whether consciously acknowledged or not–naturally think twice about approaching the man they were badmouthing behind his back (so badly . . .). Hence a lack of mutual attraction between Gatsby and the perhaps lion-share of his partying and puking own public, would be understandable.

But, as I said, Gatsby didn’t throw those parties to be sociable and merciful to all those semi-alcoholic yuppie New Yorkers who were suffering so very “terribly” under the ostensibly-crushing yoke of the ostensibly-effective Prohibition. The real but hidden function of Gatsby’s typical party was to seduce all those alcohol-craving party folks with a seemingly-endless stream of free booze and–in return for this seemingly purely-charitable and no-strings-attached kind of service–they, in fact, were to act as impromptu and uncoordinated actors in a grand theatrical spectacle serving to attract the attention of the only potential guest Gatsby was really interested in meeting. Hence, from the perspective of all those party people who had managed to find out what the real but hidden purpose had been of all of those parties they had attended with so much abandon, after the awareness had sunk in that they had allowed their previously-unaware selves be manipulated as boozed-up puppets without strings, they would arguably have valid reason to retrospectively feel used by Gatsby.

Then again, those who were more clearheaded and sober-minded about it, might also come to reason that visiting Gatsby’s parties ultimately had been a somewhat fair business deal: Their visit had already been vindicated when they had gotten their free booze. In return, all they had to do was to make merry noise, the more, the better; they had used Gatsby, and Gatsby had used them (albeit secretly). And so, in regards to this kind of party people, they would be as much inclined to go to Gatsby’s funeral as they would be inclined to attend the funeral of the owner of–let’s say–their favorite supermarket, if he would happen to also pass away. It’s possible, in principle, and in some cases no doubt will happen, but–in general–it’s not a very likely outcome.

In addition, you have the allergy for illegality-factor. For those who only knew Gatsby from the parties he had been hosting, to show up at his funeral would almost immediately draw the suspicion unto themselves that they would be consumers of an illegal substance (or even worse than consumers, traffickers, gangsters, . . .). Hence, from such a perspective it also would be quite understandable if there would be appallingly-little enthusiasm for attending the funeral of a Gatsby who had had no qualms to act as a purveyor of what regardless was still very much an illegal substance. Gatsby would be what Tom deridingly called a “filthy bootlegger“ (p.77). Why even risk being recognized by the kind of press which froths at the proverbial mouth thirsting for bigger-and-bigger audiences and which thereby seems bedeviled by an absolutely heedless and merciless predatory appetite? (their work ethic snugly being founded on the cutthroat saying: sensation = sales)

But even if alcohol had remained perfectly legal and even if all those party folks had remained entirely oblivious of Gatsby’s secret affair with Daisy, if the real reason as to why he threw his parties had escaped them entirely, then—regardless—ever since this whole ugly “hit and run” affair had taken place and consequently the almost perfectly-unknown host had been painted in such ghastly repellent light, there suddenly now was ample cause for them to lose what little nerve they might have had. Why risk damaging your own precious image while granting acte de présence on the service that gives the final salute to a man who supposedly turned out to have been such an evil crook? Whether they knew that they had been used by Gatsby or not, they would have enough reason to prefer to not get mixed up with what had become such an embarrassingly-nasty deal, one that was receiving only bad press — and who wants bad press?

Why Meyer Wolfsheim failed to show up at Gatsby’s funeral

Aside from categorically-unwilling party-people, even his discoverer, his underworld benefactor and protector–his gangster guardian, Meyer Wolfsheim–failed to attend the last service of what may very well have been his most precious and lucrative “business associate”. However, from his perspective, from the perspective of a gangster who–almost as a matter of principle–would prefer to maintain an as low a public profile as would be reasonably possible, it already should be quite understandable why he would choose against doing something which would be tantamount to sticking out his proverbial neck.

Whereas–initially–Gatsby had been such a deliberate magnet of human attention, now that this gruesome and callous “crime” had been pinned on Gatsby, under the crushing weight of bad press, as a result, his human magnet had effectively come to switch its polarity of radiation. Specifically, whereas his human magnet had been switched on in a people–attraction~mode while Daisy was not yet captured; then, once captured, he deliberately had it switched off altogether, wanting as little public attention as possible after the affair had begun and which had to be conducted ideally in perfect secrecy; then, after Gatsby was killed and the predatory press had made such a bloody mess of the whole terrible thing, his name had been brought to ruin and it was therefore as if his human beacon had suddenly switched on again–in a symbolic sense–but this time was operating as an human anti–magnet. The human gravity device had turned on in a people–repellent~mode — whereas before, people flocked to Gatsby by the droves, they were now severely repelled from associating in any way with the name of Gatsby and so probably would be strongly inclined to find granting the hideous man his last service so very undeserving.

After the unfortunate former lover of Daisy had been decimated by the press, nobody–except for genial and faithful old Nick–would be willing to voluntarily associate themselves with the legacy of Gatsby. One likely prominent fear was that their own names might end up tainted because of it. And so the prospect of attending Gatsby’s funeral, the ultimate fertile ground for gossip and rumors (with photographic evidence to boot, courtesy of the predatory paparazzi), must have been universally unattractive.

In particular, since he was the most significant indirect facilitator of Gatsby’s huge human beacon (combined with the sensitive fact that he was an automatically publicity-shy gangster), it would be perfectly-understandable why Meyer Wolfsheim would naturally sense the people-repelling force of Gatsby’s symbolically-reactivated human anti–magnet most strongly.

Why even Daisy failed to show up at Gatsby’s funeral

Of all the people who didn’t pay the man his last respects, what beyond a shadow of doubt was most dramatic of the whole fiasco was that even darling Daisy failed to show up. Indeed, her absence was most striking, as she had neither bothered to send a card with a notification of condolences, nor had she sent any other means to convey her condolences; in fact, “from Daisy, not even a flower.“ (p.129) Daisy, the dearly-beloved Daisy who had gone to become the very reason for his existence, the sole reason why he had to have had exerted himself in such extraordinary fashion in order to acquire the extraordinary amount of wealth needed, or which he thought he needed, to have a chance to win her hand, for good.

Why did Daisy choose to not show herself at Gatsby’s last honor? For one thing, by getting himself killed, she could very well be grateful for Gatsby to so completely have sacrificed himself, his life and his name, all for her benefit. Indeed, she could very well also have felt guilty for having been too cowardly to stand up for the truth and–by also deliberately keeping the authorities in the dark–to have allowed Myrtle’s accident be classified as a crime: manslaughter or even murder. She could very well have harbored guilt for allowing Gatsby to take all the blame as if he were the designated scapegoat and, courtesy of a predatory press, to have his name slaughtered. By sacrificing his life so utterly, by giving his life and his name to ensure that Daisy remained unharmed in a legal sense, was clearly something she could be grateful for. Even though it had been entirely unintentional and unplanned from his end, one might say that there was a certain nobility for Gatsby to give his life and his name for the sake of the woman he loved.

Then again, if Daisy would contemplate a little bit about the nature of her experience with Gatsby, she might find–to her consolation–that her lover had not been perfectly noble. While Gatsby had loved Daisy, yes, he had also loved her in an egocentric kind of way in the sense that he had seen himself selfishly-entitled to lay claim of Daisy’s heart entirely and exclusively — as if she effectively had had no say in the matter herself. It seems that most of all, Gatsby had loved some sort of imaginary dream world in which he and Daisy were happily wed in eternal bliss. And while, I suppose, on the one hand, it’s fine to have dreams and to cherish and pursue them to certain reasonable extent, on the other hand, it’s also important to stay realistic and grounded in truth.

By not even accommodating into his worldview the nonetheless very real given that Daisy had a life of her own, involving a husband and a little child, Gatsby had in effect ignored–“convenient” in an egocentric way–the nevertheless salient fact that Daisy was another full human being, a potentially independently-acting whole other person. It seems that Gatsby more than anything had been enthralled to his favorite Dream-pot-idol, the obsessively-idolized dream in which he and Daisy together floated off on a cloud into an ecstatic future . . . but it had been his cloud, his imagination, his egocentric fantasy.

Gatsby had wanted it all, he wanted the wealth and he wanted Daisy for a wife, not for just having an affair with. And for that reason he didn’t want to run off with her in secret as she suggested. As he told her, “that wouldn’t be respectable.“ (p.82) This must have been very important to him, to show the world that he was respectable. That’s why he wanted her to tell Tom and she never loved him, divorce Tom, get married with him in perfectly respectable manner and get on with it, get on with living in the euphoric yet respectable marital union about which he had been dreaming of for the last five years. If he would officially have Daisy for a wife, then he could also show her off to the world as his Trophy-wife and do so in perfectly respectable fashion. Perhaps this was the extent of Gatsby’s real dream, one that he as yet had not dared to openly admit to, the kind of dream in which he would live in a respectable world of upper-class wealth and the kind of dream in which he would be able to openly bask in the glory of his beautiful upper-class wife, and to thereby finally be able to legitimately lay claim to the exceptional social recognition–the luscious luxurious kind of respectability–which he had been waiting for, yearning for, all his bereft tormented life.

As such, Gatsby might posthumously be reproached for having given precedence to his hypnotizing dream of an existence in which Daisy featured prominently, yes, but chiefly in the capacity of being a cherished trophy rather than that he would grant her recognition as a fully-human consort coming with full autonomy: full individuality and full independence. Therefore, Daisy might resent Gatsby for his failure, his effective refusal, to view her as a willful human being perfectly capable of acting on her own. While Daisy would have reason to feel guilty and grateful toward Gatsby for the noble sacrifices he effectively made for her, she would also have cause to resent him for his ambitions to use her as a prop–albeit the main prop–to fulfill his fanciful dream.

If Daisy in fact did choose to side with her husband instead of Gatsby, as for any concrete (other) reasons as to why she would have done so, it is entirely possible that her love for her daughter was so strong that she didn’t want to risk losing her by fleeing into the arms of–what Tom might very well be able to prove in a divorce court was–a criminal, a bootlegging criminal and gangster front-man even. Furthermore, while she might not have loved Tom anymore at that time, she might have reasoned that at least his temper was less volatile than Gatsby’s — whose exhibition of rage had left the young mother in a petrifying shock. As such, she could began to feel indebted towards her husband for his willingness to forgive his wife for her marital indiscretion — something which, after Gatsby’s outburst down at the Plaza, she might be tempted to judge as something that had been indiscreet, indeed. In addition, the fact that they had been involved in the death of Myrtle and the fright and the guilt which this even more shocking event must have brought down upon her could very well have zapped what good feelings she might still have had for Gatsby. Indeed, the ordeal may have squashed her good feelings in general (and might be keeping her in such a debilitating state for quite some time to come).

If it is true that Tom’s conception of love chiefly consists of a sense of indebtedness (guilt) then by having caught his wife being unfaithful, he now has succeeded in having his love being reciprocated. Before Daisy’s affair with Gatsby, courtesy of his rather pronounced habit of infidelity, Tom must have exclusively felt indebted toward his wife (and increasingly so, the more he slept around). But ever since Daisy’s affair had come to light, he would have reason to consider her likewise being indebted to him, specifically for his “magnanimous” willingness to take her back.

The question remains though, will their marriage ever come to revolve around true love? — real unconditional love? — the durable and stable kind of love that would be marked by intimacy and mutual trust? Or is mutual indebtedness, rooted in mutual guilt and therefore rooted in mutual fear, punitive fear, fear for being shamed, the best they can ever do? Would Tom be able to make himself into the better man–a more caring, faithful and intimate man–that he promised Daisy he would now become, or will he secretly continue to (slavishly) succumb to the carnal temptations of life?

Daisy Darling . . .